Two of the best-known labor economists in the US, Lawrence F. Katz and Alan B. Krueger, recently published a study of the rise of so-called alternative work arrangements.

Here is what they found:

The percentage of workers engaged in alternative work arrangements – defined as temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, contract workers, and independent contractors or freelancers – rose from 10.1 percent [of all employed workers] in February 2005 to 15.8 percent in late 2015.

That is a huge jump, especially since the percentage of workers with alternative work arrangements barely budged over the period February 1995 to February 2005; it was only 9.3 in 1995.

But their most startling finding is the following:

A striking implication of these estimates is that all of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements. Total employment according to the CPS increased by 9.1 million (6.5 percent) over the decade, from 140.4 million in February 2005 to 149.4 in November 2015. The increase in the share of workers in alternative work arrangements from 10.1 percent in 2005 to 15.8 percent in 2015 implies that the number of workers employed in alternative arrangement increased by 9.4 million (66.5 percent), from 14.2 million in February 2005 to 23.6 million in November 2015. Thus, these figures imply that employment in traditional jobs (standard employment arrangements) slightly declined by 0.4 million (0.3 percent) from 126.2 million in February 2005 to 125.8 million in November 2015.

Take a moment to let that sink in—and think about what that tells us about the operation of the US economy and the future for working people. Employment in so-called traditional jobs is actually shrinking. The only types of jobs that have been growing in net terms are ones in which workers have little or no security and minimal social benefits.

Figure 2 from their study shows the percentage of workers in different industries that have alternative employment arrangements. The share has grown substantially over the last ten years in almost all of them. In Construction, Professional and Business Services, and Other Services (excluding Public Services) approximately one quarter of all workers are employed using alternative work arrangements.

The study

Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics has not updated its Contingent Work Survey (CWS), the authors contracted with the RAND institute to do their own study. Thus, Rand expanded its own American Life Panel (ALP) surveys in October and November 2015 to include questions similar to those asked in the CWS. They surveys only collected information about the surveyed individual’s main job. And, to maintain compatibility with the CWS surveys, day laborers were not included in the results. Finally, the authors only included information from individuals who had worked in the survey reference week.

People were said to be employed under alternative work arrangements if they were “independent contractors,” “on-call workers,” “temporary help agency workers,” or “workers provided by contract firms. The authors defined these terms as follows:

“Independent Contractors” are individuals who report they obtain customers on their own to provide a product or service as an independent contractor, independent consultant, or freelance worker. “On-Call Workers” report having certain days or hours in which they are not at work but are on standby until called to work. “Temporary Help Agency Workers” are paid by a temporary help agency. “Workers Provided by Contract Firms” are individuals who worked for a company that contracted out their services during the reference week.

The results in more detail

All four categories of nonstandard work recorded increases:

Independent contractors continue to be the largest group (8.9 percent in 2015), but the share of workers in the three other categories more than doubled from 3.2 percent in 2005 to 7.3 percent in 2015. The fastest growing category of nonstandard work involves contracted workers. The percentage of workers who report that they worked for a company that contracted out their services in the preceding week rose from 0.6 percent in 2005 to 3.1 percent in 2015.

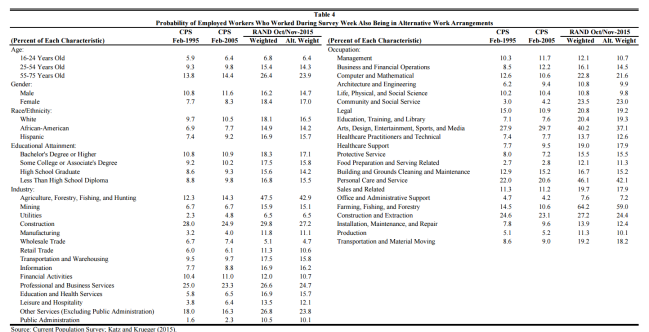

Table 4 shows the percentage of workers in different categories that are employed for their main job in one of the four nonstandard work arrangements. The relevant comparisons over time are with the two CPS studies and the Alternative Weighted results from the Rand study.

Here are some of the main findings:

There is a clear age gradient that has grown stronger, with older workers more likely to have nonstandard employment than younger workers. In 2015, 6.4 percent of those aged 16 to 24 were employed in an alternative work arrangement, while 14.3 percent of those aged 25-54 and 23.9 percent of those aged 55-74 had nonstandard work arrangements.

The percentage of women with nonstandard work arrangements grew dramatically from 2005 to 2015, from 8.3 percent to 17 percent. Women are now more likely to be employed under these conditions than men.

Workers in all educational levels experienced a jump in nonstandard work, with the increase greatest for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. “Occupational groups experiencing particularly large increases in the nonstandard work from 2005 to 2015 include computer and mathematical, community and social services, education, health care, legal, protective services, personal care, and transportation jobs.”

The authors also tested to determine “whether alternative work is growing in higher or lower wage sectors of the labor market.” They found that “workers with attributes and jobs that are associated with higher wages are more likely to have their services contracted out than are those with attributes and jobs that are associated with lower wages. Indeed, the lowest predicted quintile-wage group did not experience a rise in contract work.”

The take-away

The take-away is pretty clear. Corporate profits and income inequality have grown in large part because US firms have successfully taken advantage of the weak state of unions and labor organizing more generally, to transform work relations. Increasingly workers, regardless of their educational level, find themselves forced to take jobs with few if any benefits and no long-term or ongoing relationship with their employer. Only a rejuvenated labor movement, one able to build strong democratic unions and press for radically new economic policies will be able to reverse existing trends.

Not sure what this post adds beyond providing a link and a few quotes from an important study. The conclusion, “Only a rejuvenated labor movement, one able to build strong democratic unions and press for radically new economic policies will be able to reverse existing trends,” has no validity. Many years ago it did, but there has not been a major economic or social welfare reform for working people since the early 1970s. Struggle has continued, nearly all defensive in an attempt to stop or slow down the decline in standards of life, work, and retirement. But “radically new economic policies” are only possible with the same kind of change that people confronted in tsarist Russia and old China.

LikeLike

Actually the info lines up with the decline in unions, a deliberate strategy by corporate forces and the 1%.

LikeLike

Thanks for alerting us to this paper, Marty! I’ve sent it along to others working academically and politically on irregular work schedules, in Oregon and elsewhere.

Along with the rest of the findings, this paper highlights the crying need for our large surveys of wages and working conditions to ask questions not included here, on schedules that vary wildly by day and time over the week, that change dramatically from week to week, and for which workers receive very short notice. Other big issues are insufficient hours and being sent home early when business is slow.

Mary King, Portland, Oregon

*************************************************************************************** Mary King maryking219@gmail.com

***************************************************************************************

On Wed, Dec 28, 2016 at 12:53 PM, Reports from the Economic Front wrote:

> mhl posted: “Two of the best-known labor economists in the US, Lawrence > F. Katz and Alan B. Krueger, recently published a study of the rise of > so-called alternative work arrangements. Here is what they found: The > percentage of workers engaged in alternative work ” >

LikeLike

I’m thinking the conclusions don’t follow from the detail. My naive expectation was that the growth in non-traditional positions would have taken place among the young and poorly-paid – the usual waiters-and-bartenders plaint. The details suggest otherwise: much of the growth seems to have been among older people (driven to cover shortfalls in retirement income, and/or retired professionals that “consult” in their industries) and skilled people. Skilled people include computer programmers, many, many of whom are placed by (ripoff) agencies, or contract themselves out, by choice or circumstance. I’d like to see someone review the figures with these groups in mind. In any event, there’s no obvious case that more unionism would affect these arrangements.

LikeLike

Those who doubt that the decline of trade union countervailing power in the US (and UK) is a key variable in this process,should review the wider evidence for the long terms decline of decently paid jobs with real promotion prospects and adequate pension arrangements etc, and note that it closely parallels the long-term impact of neoliberal anti-union legislation and propaganda, and the associated privatisation and the contracting-out of former state jobs and assets, bringing more workers into the traditionally less-unionised private and increasingly arms-length contract labour sectors. Of course, correlation is not necessarily causation, but finding a more plausible causal explanation has been extremely hard for ardent anti-union neoliberals, aside from the suggestion that these people actively seek and/or deserve low pay and poor working conditions in order to avoid what would otherwise be ‘voluntary unemployment.’

The real difficulty is in overturning the neoliberal consensus supported by so many of those who suffer the most from the relentless shifting of wealth and power upwards to higher income and status groups, and especially the 1%. Trump has no advertised solutions for this since his version of protectionist neoliberlism leaves the power centres of domestic neoliberalism in place, while threatening to close the borders and start trade wars. ‘Bringing back American jobs’ into a still largely neoliberal context dominated by the wealth and power of the 1% will simply create more (although how many more is an interesting question, since trade wars can reduce domestic employment) low paid arms-length marginal jobs.

Although focussed on the tax rther than unions diimension, here is a recent UK study of the wider problem:

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/poverty-jobs-johnes/utm_content=buffer3a1eb&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=buffer

LikeLike

The chart didn’t make sense to me as there was an increased percentage of workers in most categories in 2015 vs 2005 and 1995. If it increased significantly in so many categories then it must have decreased significantly in other, right? And in fact, if you add up the percentages in the green 2015 bars, they total almost 185%! What am I missing?

LikeLike

The overall percentage of workers with so-called alternative employment arrangements was estimated as 15.8 percent in 2015. If you look at Chart 2, you will see that there are six industry categories where the percentage of workers employed in such arrangements is over 15 percent and seven where it is below 15 percent. Not all industries employ the same number of people; the estimated percentage comes from a weighted average of all the industries.

LikeLike

Hmm. So I am concerned about the judgement behind the conclusion that any of these non-traditional “workers” have jobs with little or no security and minimal social benefits. Before I chose to become an independent contractor, a very wise CPA explained to me that when someone else is signing my checks, my security is in their hands. When I am signing the paycheck, its up to me how much I make and how often I get paid. Ironically, that’s the philosophy behind the free enterprise system. And until the social benefits outweigh the tax advantages of being self-employed… its a pretty easy decision to make, especially when you take into account the lack of gender equality when it comes to compensation, the rising cost of healthcare and the greed of corporate America.

LikeLike

Pingback: American Capitalism Is Already Abysmal — Trump Is About to Make It a Lot Worse – Common Dreams (press release)

Reblogged this on Whereof One Can Speak and commented:

Quote: “Corporate profits and income inequality have grown in large part because US firms have successfully taken advantage of the weak state of unions and labor organizing … to transform work relations. Increasingly workers, regardless of their educational level, find themselves forced to take jobs with few if any benefits and no long-term or ongoing relationship with their employer.”

LikeLike

Pingback: American Capitalism Is Already Abysmal — Trump Is About to Make It a Lot Worse | MIDTOWN SOUTH COMMUNITY COUNCIL

Pingback: The rise of the bad jobs economy « WORDVIRUS

Pingback: Organize the White Working Class! | Be Freedom

Pingback: The Real Beneficiaries of Donald Trump's Fake Populism – Liberal View News

Pingback: If You Think Trump's at War With the Deep State, Take Another Look at His Policies – In These Times – Oz Bush Telegraph Online

Pingback: If You Think Trump’s at War With the Deep State, Take Another Look at His Policies | Cuba on Time

Pingback: The potential reality of basic income schemes – DPAC